Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang | |

|---|---|

諸葛亮 | |

An illustration of Zhuge Liang | |

| Imperial Chancellor of Shu Han | |

| In office 229 – September or October 234 | |

| In office May 221 – 228 | |

| Monarch | Liu Bei / Liu Shan |

| General of the Right | |

| In office 228–229 | |

| Monarch | Liu Shan |

| Governor of Yi Province | |

| In office 223 – September or October 234 | |

| Monarch | Liu Shan |

| Succeeded by | Jiang Wan (as Inspector) |

| Colonel-Director of Retainers | |

| In office 221 – September or October 234 | |

| Monarch | Liu Bei / Liu Shan |

| Preceded by | Zhang Fei |

| Deputy Head of the Secretariat | |

| In office 221 – September or October 234 | |

| Monarch | Liu Bei / Liu Shan |

| Succeeded by | Jiang Wan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 181 Yinan County, Shandong |

| Died | September or October 234 (aged 53)[a][1] Wuzhang Plains, Shaanxi |

| Resting place | Mount Dingjun, Shaanxi |

| Spouse | Lady Huang |

| Relations |

|

| Children |

|

| Parent |

|

| Occupation | Statesman, military leader, scholar, inventor |

| Courtesy name | Kongming (孔明) |

| Posthumous name | Marquis Zhongwu (忠武侯) |

| Peerage | Marquis of Wu District (武鄉侯) |

| Nicknames | "Sleeping Dragon" (臥龍 / 伏龍) |

| Zhuge Liang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 諸葛亮 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 诸葛亮 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 孔明 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zhuge Liang (ⓘ) (181 – September or October 234),[a] also commonly known by his courtesy name Kongming, was a Chinese statesman, strategist, and inventor who lived through the end of the Eastern Han dynasty (c. 184–220) and the early Three Kingdoms period (220–280) of China. During the Three Kingdoms period, he served as the Imperial Chancellor (or Prime Minister) of the state of Shu Han (221–263) from its founding in 221 and later as regent from 223 until his death in September or October 234.[1]

He is recognised as the most accomplished strategist of his era. His reputation as an intelligent and cultured scholar grew even while he was living in relative seclusion, earning him the nickname "Wolong" or "Fulong" (both meaning "Sleeping Dragon").

Zhuge Liang's methods of administration drew both from Legalism[2] as well as Confucianism.[3] He was critical of the Legalist thought of Shang Yang,[4] and advocated benevolence and education as tenets of being a ruler.[5] He compared himself with Guan Zhong,[2] developing Shu's agriculture and industry to become a regional power.[6] He attached great importance to the works of Shen Buhai and Han Fei,[3] refusing to indulge local elites and adopting strict, but fair and clear laws. In remembrance of his governance, local people maintained shrines to him for ages.[7]

Zhuge is an uncommon two-character Chinese compound family name. In 760, when Emperor Suzong of the Tang dynasty built a temple to honour Jiang Ziya, he had sculptures of ten famous historical military generals and strategists placed in the temple flanking Jiang Ziya's statue: Zhuge Liang, Bai Qi, Han Xin, Li Jing, Li Shiji, Zhang Liang, Sima Rangju, Sun Tzu, Wu Qi, and Yue Yi.[8]

Historical sources

[edit]

The authoritative historical source on Zhuge Liang's life is his biography in Volume 35 of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi), which was written by the historian Chen Shou (233–297) in the third century. Chen Shou had worked in the historical offices of the Shu Han government, and had previously collated Zhuge Liang's writings into an anthology.[Sanguozhi 1] The scope of this collection may have been limited to official government documents.[9]: 113

In the fifth century, the Liu Song dynasty historian Pei Songzhi (372–451) annotated the Sanguozhi by incorporating information from other sources to Chen Shou's original work and adding his personal commentary. Some alternative texts used in the annotations to the Sanguozhi include:

- Xiandi Chunqiu (獻帝春秋; Chronicles of Emperor Xian) by Yuan Wei (袁暐)

- Han Jin Chunqiu (漢晉春秋; Chronicles of Han and Jin) by Xi Zuochi

- Xiangyang Ji (襄陽記; Records of Xiangyang) by Xi Zuochi

- Wei Shu (魏書; Book of Wei) by Wang Chen, Xun Yi and Ruan Ji

- Weilüe (魏略; Brief History of Wei) by Yu Huan

- Wei Shi Chunqiu (魏氏春秋; Chronicles of the Ruling Family of Wei) by Sun Sheng

- Jin Yang Qiu (晉陽秋) by Sun Sheng

- Yuanzi (袁子) by Yuan Zhun (袁準)

- Shu Ji (蜀記; Records of Shu) by Wang Yin (王隱)

- Wu Shu (吳書; Book of Wu) by Wei Zhao

- Lingling Xianxian Zhuan (零陵先賢傳; Biographies of the Departed Worthies of Lingling)

During the Qing dynasty, the historian Zhang Zhu (張澍; 1776–1847) compiled and arranged multiple pieces of literature on Zhuge Liang into an 11-volume collection called Zhuge Zhongwu Hou Wen Ji (諸葛忠武侯文集; Literature Collection of Marquis Zhuge Zhongwu). The collection contained, among other things, a preface by Zhang Zhu, Zhuge Liang's biography from the Sanguozhi, Zhuge Liang's writings, imperial edicts issued to Zhuge Liang, and appraisals of Zhuge Liang. In 1960, Duan Xizhong (段熙仲) and Wen Xuchu (聞旭初) annotated and reorganised Zhang Zhu's original collection, and had it published by the Zhonghua Book Company under the title Zhuge Liang Ji (諸葛亮集; Collected Works of Zhuge Liang).

Family background

[edit]Zhuge Liang's ancestral home was in Yangdu County (陽都縣), Langya Commandery (琅邪郡), near present-day Yinan County or Yishui County, Shandong.[10] There are two other accounts of his ancestral origins in the Wu Shu (吳書) and Fengsu Tongyi (風俗同意).

The Wu Shu recorded that his ancestral family name was actually Ge (葛) and his ancestors were originally from Zhu County (諸縣; southwest of present-day Zhucheng, Shandong) before they settled in Yangdu County. As there was already another Ge family in Yangdu County before they came, the locals referred to the newcomers as the Zhuge – combining Zhu (County) and Ge – to distinguish them from the other Ge family. Over time, Zhuge Liang's ancestors adopted Zhuge as their family name.[Sanguozhi zhu 1]

The Fengsu Tongyi recorded that Zhuge Liang's ancestor was Ge Ying (zh:葛嬰), who served under Chen Sheng, a rebel leader who led the Dazexiang uprising against the Qin dynasty. Chen Sheng later executed Ge Ying.[11] During the early Western Han dynasty, Emperor Wen considered that Ge Ying was unjustly put to death so he enfeoffed Ge Ying's grandson as the Marquis of Zhu County to honour Ge Ying. Over time, Ge Ying's descendants adopted Zhuge as their family name by combining Zhu (County) and Ge.[Sanguozhi zhu 2]

The earliest known ancestor of Zhuge Liang who bore the family name Zhuge was Zhuge Feng (諸葛豐), a Western Han dynasty official who served as Colonel-Director of Retainers (司隷校尉) under Emperor Yuan (r. 48–33 BCE). Zhuge Liang's father, Zhuge Gui (諸葛珪), whose courtesy name was Jungong (君貢), served as an assistant official in Taishan Commandery (泰山郡; around present-day Tai'an, Shandong) during the late Eastern Han dynasty under Emperor Ling (r. 168–189 CE).[Sanguozhi 2]

Zhuge Liang had an elder brother, a younger brother, and two elder sisters. His elder brother was Zhuge Jin[Sanguozhi 3] and his younger brother was Zhuge Jun (諸葛均).[Sanguozhi 4] The elder of Zhuge Liang's two sisters married Kuai Qi (蒯祺), a nephew of Kuai Yue and Kuai Liang.[12] While the younger one married Pang Shanmin (龐山民), a cousin of Pang Tong.[Sanguozhi zhu 3]

Physical appearance

[edit]The only known historical description of Zhuge Liang's physical appearance comes from the Sanguozhi, which recorded that he was eight chi tall (approximately 1.84 metres (6 ft 0 in)) with "a magnificent appearance" that astonished his contemporaries.[Sanguozhi 5]

In later sources, it is said that during the northern expedition, Zhuge Liang commanded the three armies with a white feather fan while wearing a headscarf made of kudzu cloth and riding on a plain chariot.[13][14]

The Moss Roberts' translation of the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Zhuge Liang's appearance is described as follows:

Kongming appeared singularly tall, with a face like gleaming jade and a plaited silken band around his head. Cloaked in crane down, he had the buoyant air of a spiritual transcendent.

The original Chinese text in the novel mentions that Zhuge Liang wore a guanjin (綸巾; a type of headscarf or hat) and a hechang (鶴氅; a robe commonly worn by Daoists).[15]

Early life (181–207)

[edit]As Zhuge Liang was orphaned at a young age, he was raised by Zhuge Xuan, one of his father's cousins. He accompanied Zhuge Xuan to Yuzhang Commandery (豫章郡; around present-day Nanchang, Jiangxi) when the latter was appointed as the Commandery Administrator sometime in the mid-190s.[Sanguozhi 4] Later, after the Han central government designated Zhu Hao as the new Administrator, Zhuge Xuan left Yuzhang Commandery and brought Zhuge Liang and Zhuge Jun to Jing Province (covering present-day Hubei and Hunan) to live with the provincial governor Liu Biao, whom he was an old friend of.[Sanguozhi 6][1]

After Zhuge Xuan died, Zhuge Liang moved to Deng County (鄧縣) in Nanyang Commandery (南陽郡), and settled down in Longzhong (隆中), an area about 20 li west of Xiangyang, the capital of Jing Province.[Sanguozhi zhu 4] In Longzhong, he lived the life of a peasant and spent his free time reading and travelling. He enjoyed reciting Liangfu Yin (梁父吟),[Sanguozhi 7] a folk song popular in the area around his ancestral home in Shandong. Zhuge Liang maintained close relations with well-known intellectuals such as Sima Hui, Pang Degong and Huang Chengyan.[1] However, other local literati scorned him when they learnt that he often compared himself to Guan Zhong and Yue Yi. Only a few, namely Cui Zhouping (崔州平),[b] Xu Shu, Shi Tao (石韜) and Meng Jian (孟建), got along well with him and agreed that he was comparable to Guan Zhong and Yue Yi.[Sanguozhi 8][Sanguozhi zhu 6]

Between the late 190s and early 200s, Zhuge Liang often studied and travelled with Xu Shu, Shi Guangyuan and Meng Gongwei. Whenever he read, he only picked up the key points and moved on. His three friends, in contrast, focused on details and sometimes even memorised them.[Sanguozhi zhu 6] Throughout his time in Longzhong, he led a carefree life and took his time to do things. He often sat down with his arms around his knees, sighing to himself from time to time while in deep thought. He once told his three friends that they would become commandery administrators or provincial governors if they served in the government. When they asked him what his ambition was, he only laughed and did not give an answer.[Sanguozhi zhu 7]

Meeting with Liu Bei (207–208)

[edit]Recommendation from Sima Hui and Xu Shu

[edit]At the time, the warlord Liu Bei was living in Xinye County as a guest of Liu Biao, the governor of Jing Province. During this time, he met the hermit Sima Hui and consulted him on the affairs of their time. Sima Hui said, "What do Confucian academics and common scholars know about current affairs? Only outstanding talents have the best understanding of current affairs. In this region, there are two of such talents: Crouching Dragon and Young Phoenix." When Liu Bei asked him who "Crouching Dragon" and "Young Phoenix" were, Sima Hui replied, "Zhuge Kongming and Pang Shiyuan."[Sanguozhi zhu 8] Xu Shu, whom Liu Bei regarded highly, also recommended Zhuge Liang by saying, "Zhuge Kongming is the Crouching Dragon. General, don't you want to meet him?"[Sanguozhi 9] When Liu Bei asked Xu Shu if he could bring Zhuge Liang to meet him, Xu Shu advised him to personally visit Zhuge Liang instead of asking Zhuge Liang to come to him.[Sanguozhi 10]

Liu Bei's three visits

[edit]

The Sanguozhi recorded in just one sentence that Liu Bei visited Zhuge Liang three[c] times and met him.[Sanguozhi 11] The Zizhi Tongjian recorded that the meeting(s) took place in 207.[16] Chen Shou also mentions the three visits in his biographical sketch of Zhuge Liang appended to the memoirs Chen Shou compiled.[Sanguozhi 12]

During their private meeting, Liu Bei sought Zhuge Liang's advice on how to compete with the powerful warlords and revive the declining Han dynasty.[Sanguozhi 13] In response, Zhuge Liang presented his Longzhong Plan, which envisaged a tripartite division of China between the domains of Liu Bei, Cao Cao and Sun Quan. According to the plan, Liu Bei should seize control of Jing Province (covering present-day Hubei and Hunan) and Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing) from their respective governors, Liu Biao and Liu Zhang, and establish a solid foothold in southern and western China. Liu Bei would then form an alliance with Sun Quan, who ruled eastern China, and wage war against Cao Cao, who controlled northern China and the political centre of the Han dynasty in central China.[Sanguozhi 14]

After the meeting, Liu Bei became very close to Zhuge Liang and spent much time with him – much to Guan Yu and Zhang Fei's chagrin. Liu Bei explained to them, "Now that I have Kongming, I am like a fish that has found water. I hope you'll stop making unpleasant remarks." Guan Yu and Zhang Fei then stopped complaining.[Sanguozhi 15]

Formation of the Sun–Liu alliance (208–209)

[edit]Liu's evacuation to Xiakou

[edit]

In the autumn of 208,[16] shortly before Liu Biao's death, Cao Cao led his forces on a southern campaign to conquer Jing Province. When Cao Cao's forces reached Jing Province's capital Xiangyang, Liu Biao's younger son Liu Cong, who had succeeded his father as the Governor of Jing Province, surrendered to Cao Cao. Upon receiving news of Liu Cong's surrender, Liu Bei immediately evacuated his base in Fancheng (樊城; present-day Fancheng District, Xiangyang, Hubei) and led thousands of his followers, both military and civilian, on a journey to Xiakou (夏口; in present-day Wuhan, Hubei) to join Liu Biao's elder son Liu Qi. Along the way, Cao Cao's forces caught up with them and defeated them at the Battle of Changban. Along with only a handful of close followers, Liu Bei managed to escape, and upon reaching Xiakou sent Zhuge Liang as his representative to meet Sun Quan and discuss an alliance against Cao Cao.[16][Sanguozhi 16]

Meeting with Sun Quan

[edit]Around the time, Sun Quan was in Chaisang (柴桑; southwest of present-day Jiujiang, Jiangxi) and had been closely observing the developments in Jing Province.[Sanguozhi 17] When Zhuge Liang met Sun Quan, he said:

The land is in chaos. General, you raised an army and occupied Jiangdong, while Liu Bei is gathering forces at the south of the Han River. Both of you are preparing to compete with Cao Cao for control over China. As of now, Cao Cao has eliminated internal threats, more or less pacified his lands, and led his forces south to occupy Jing Province. The Empire trembles at his might. A hero without opportunity to display his prowess, Liu Bei has retreated here. I hope that you, General, will carefully assess your strengths and decide your next course of action. If you decide to lead your forces from the Wu and Yue regions to resist the Central States, you should quickly break ties [with Cao Cao]. If you can't resist him, why don't you put down your weapons, remove your armour, position yourself as subordinate, and serve him? General, although by appearances you seem ready to pledge allegiance to Cao Cao, in your heart you still harbour thoughts of freedom. If you can't be decisive at such a crucial moment, it will be no time until you meet with disaster![Sanguozhi 18]

When Sun Quan asked him why Liu Bei did not surrender to Cao Cao,[Sanguozhi 19] Zhuge Liang replied:

Tian Heng was nothing more than a mere warrior from Qi, yet he remained faithful and refused to surrender. Shouldn't we expect more from Liu Bei, scion of the royal house of Han? His heroism and talents are renowned throughout the world. Gentlemen and commoners alike honour and admire him. Like the rivers returning to the sea; like the upheavals in the affairs of our time, this is Heaven's doing. How could he turn his back on that and serve Cao Cao?[Sanguozhi 20]

An enraged Sun Quan then said that he would not allow anyone but himself to rule the territories and people in Wu. When he asked Zhuge Liang how Liu Bei could expect to resist Cao Cao, given his recent defeat at Changban,[Sanguozhi 21] Zhuge Liang replied:

Liu Bei's forces may have suffered a defeat at Changban, but now many of his men who were scattered during the battle are returning to him, along with 10,000 elite marine troops under Guan Yu, combining forces with Liu Qi's army of at least 10,000 from Jiangxia. Cao Cao and his forces have come a great distance and are exhausted. I have heard that his light cavalry travelled over 300 li in twenty-four hours in pursuit of Liu Bei. This fits the saying: "even a powerful arrow at the end of its flight cannot penetrate a piece of Lu silk cloth." Such a battle should be avoided according to military strategy, which says that it "will definitely result in defeat for the commander". The northerners are also not familiar with naval warfare. Although the people in Jing Province have surrendered to Cao Cao, they were forced to submit, and are not truly loyal to him. Now, General, if you are able to send your fierce officers to lead your vast hosts to align goals and combine might with Liu Bei, the defeat of Cao Cao's army is certain. Once defeated, Cao Cao will be forced to return north, and Jing Province and Wu will be sturdy as the legs of a bronze cauldron. The trigger for victory or defeat is your decision today.[Sanguozhi 22]

Zhang Zhao's recommendation

[edit]Yuan Zhun's Yuanzi recorded that when Zhuge Liang was in Chaisang, Zhang Zhao recommended he switch allegiance from Liu Bei to Sun Quan, but Zhuge Liang refused. When Zhang Zhao asked him why, Zhuge Liang said, "[Sun Quan] is a good leader of men. However, from what I observe about his character, he will make good use of my abilities but not to their fullest extent. That is why I don't want to serve under him."[Sanguozhi zhu 9]

Pei Songzhi noted how differently this episode portrayed Zhuge Liang's special and sui generis relationship with Liu Bei, and pointed out that his loyalty to Liu Bei was so firm that nothing would make him switch allegiance to Sun Quan— not even if Sun Quan could make full use of his abilities. Pei Songzhi then cited a similar example of how Guan Yu, during his brief service under Cao Cao, maintained unwavering loyalty to Liu Bei even though Cao Cao treated him very generously.[Sanguozhi zhu 10]

Battle of Red Cliffs

[edit]

After initial advisement against Zhuge Liang's plan for a Sun–Liu alliance, further consultation with his generals Lu Su and Zhou Yu convinced Sun Quan to move forward with it.[17] He ordered Zhou Yu, Cheng Pu, Lu Su and others to lead 30,000 troops to join Liu Bei in resisting Cao Cao's invasion.[Sanguozhi 23] In the winter of 208, the allied forces of Liu Bei and Sun Quan scored a decisive victory over Cao Cao's forces at the Battle of Red Cliffs.[16] Cao Cao retreated to Ye (鄴; in present-day Handan, Hebei) after his defeat.[Sanguozhi 24]

Service in southern Jing Province (209–211)

[edit]Following the Battle of Red Cliffs, Liu Bei nominated Liu Qi as the Inspector of Jing Province and sent his forces to conquer the four commanderies in southern Jing Province: Wuling (武陵; near Changde, Hunan), Changsha, Guiyang (桂陽; near Chenzhou, Hunan) and Lingling (零陵; near Yongzhou, Hunan). The administrators of the four commanderies surrendered to him.[16] After Liu Qi died in 209, acting on Lu Su's advice, Sun Quan agreed to "lend" the territories in Jing Province to Liu Bei and nominate him to succeed Liu Qi as the Governor of Jing Province.[18]

After assuming governorship of southern Jing Province in 209,[16] Liu Bei appointed Zhuge Liang as Military Adviser General of the Household (軍師中郎將) and put him in charge of collecting tax revenue from Lingling, Guiyang and Changsha commanderies for his military forces.[Sanguozhi 25] During this time, Zhuge Liang was stationed in Linzheng County (臨烝縣; present-day Hengyang, Hunan) in Changsha Commandery.[Sanguozhi zhu 11]

Conquest of Yi Province (211–214)

[edit]In 211, Liu Zhang, the Governor of Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing), invited Liu Bei to lead troops into Yi Province to assist him in countering his rival, Zhang Lu, in Hanzhong Commandery. While Liu Bei was away in Jing Province, Zhuge Liang remained behind with Guan Yu and others to guard Liu Bei's territories in Jing Province.[Sanguozhi 26]

When Liu Bei decided to take over Liu Zhang's lands in 212,[18] Zhuge Liang, along with Zhang Fei, Zhao Yun and others, led troops from Jing Province into Yi Province to reinforce Liu Bei. They conquered many counties and commanderies along the way and eventually joined Liu Bei in surrounding Chengdu, the capital of Yi Province.[Sanguozhi 27]

After Liu Zhang surrendered and relinquished control over Yi Province to Liu Bei in 214,[19] Zhuge Liang was appointed as Military Adviser General (軍師將軍) and made a staff member of the office of the General of the Left (左將軍), the nominal appointment Liu Bei held at the time.[d] Whenever Liu Bei went on military campaigns, Zhuge Liang remained behind to guard Chengdu and ensured that the city was well-stocked with supplies and well-defended.[Sanguozhi 29]

Liu's coronation (214–223)

[edit]

In late 220, some months after Cao Cao's death, his son and successor Cao Pi usurped the throne from Emperor Xian, ended the Eastern Han dynasty, and established the state of Wei with himself as the new emperor. This event marks the beginning of the Three Kingdoms period in China.[20] In the following year, Liu Bei's followers urged him to declare himself emperor to challenge Cao Pi's legitimacy, but Liu Bei refused.[Sanguozhi 30]

Zhuge said:

In the past, when Wu Han, Geng Yan and others first urged Emperor Guangwu to assume the imperial throne, Emperor Guangwu declined a total of four times. Geng Chun then told him: "The world's valiant heroes are gasping for air, hoping there is anything worth hoping for. If you don't heed everyone's advice, your associates will go back to seeking a sovereign, and no one will want to follow you anymore." Emperor Guangwu felt Geng Chun's words were profound and correct, so he accepted the throne. Now the Cao family have usurped the Han, and China has no sovereign. Your Highness,[e] from the great royal clan of Liu, you have risen to overcome the times. The appropriate action is for you to take position as emperor. Your associates who have followed your Highness at length through great effort and hardship because they too hoped for some small success, are just like the ones Geng Chun spoke of.[Sanguozhi 31]

In 221,[20] Liu Bei declared himself emperor and established the state of Shu Han. He appointed Zhuge Liang as his Imperial Chancellor (丞相) as follows:

From the misfortune of our insolvent family, we have been lofted to an office of great authority. Cautiously we approach this great enterprise, never daring to assume ease or tranquility, thinking foremost of the needs of the people, yet we fear ourselves unable to bring them peace. Alas! Imperial Chancellor Zhuge Liang will understand our intents, tirelessly redress our deficiencies, and assist in spreading our benevolent light, that it may illuminate all of China. Sir, you are thus enjoined to do so![Sanguozhi 32]

Zhuge Liang also held the additional appointment of Lu Shangshu Shi (錄尚書事), the Supervisor of the Imperial Secretariat, and had full acting imperial authority. After Zhang Fei's death in mid 221,[20] Zhuge Liang took on an additional appointment as Colonel-Director of Retainers (司隷校尉), which Zhang Fei previously held.[Sanguozhi 33]

Appointment as regent (223)

[edit]

Following his defeat at the Battle of Xiaoting in 222,[20] Liu Bei retreated to Yong'an County (永安縣; present-day Fengjie County, Chongqing) and became critically ill in early 223.[Sanguozhi 34] He summoned Zhuge from Chengdu, and told him: "Sir, you're ten times more talented than Cao Pi. You'll definitely bring peace to the Empire and accomplish our great mission. If my heir can be assisted, then assist him; if he turns out to be incompetent, then you may make your own decision."[Sanguozhi 35]

With tears in his eyes, Zhuge replied: "I'll do my utmost and serve with unwavering loyalty until death!"[Sanguozhi 36] Liu Bei then instructed Liu Shan, his son and heir apparent, as follows: "When you work together with the Imperial Chancellor, you must treat him like your father."[Sanguozhi 37] Liu Bei then named Zhuge Liang as regent for Liu Shan, and Li Yan as deputy regent. He died on 10 June 223 in Yong'an County.[Sanguozhi 38]

The last command of Liu Bei to Zhuge Liang, translated literally above as "you may make your own decision" (君可自取), is ambiguous. Chen Shou commented that Liu Bei wholeheartly trusted Zhuge Liang and was permitting him to assume leadership. Yi Zhongtian in his "Analysis of the Three Kingdoms" presented several interpretations of Liu Bei's message.[citation needed] Some argued that Liu Bei said that only to test Zhuge Liang's loyalty as his brother, Zhuge Jin, was working for Eastern Wu. Others commented that the ambiguous phrase did not mean Zhuge Liang was allowed take the throne for himself, but he was permitted to, when the situation demanded, replace Liu Shan with other of Liu Bei's living sons such as Liu Yong and Liu Li.

Following Liu Bei's death, Liu Shan ascended the throne and succeeded his father as the emperor of Shu. After his coronation, Liu Shan enfeoffed Zhuge Liang as the Marquis of Wu District (武鄉侯) and created a personal staff to assist him. Later, Zhuge Liang assumed an additional appointment as Governor of Yi Province (益州牧). He personally oversaw all state affairs and made the final call on all policy decisions.[Sanguozhi 39]

When rebellions broke out in the Nanzhong region of southern Shu, Zhuge Liang did not immediately take military action to suppress the rebellions because he thought it was not appropriate to do so in light of the recent death of Liu Bei. In late 223, he sent Deng Zhi as Shu's ambassador to Eastern Wu to make peace and rebuild the Wu–Shu alliance against Cao Wei.[22][Sanguozhi 40]

During his regency, Zhuge Liang set Shu's objective as the restoration of the Han dynasty, continuing Liu Bei's objective. He appointed large numbers of local elites as low level officials, improving relations between Liu Bei's conquest bureaucracy, local elites, and the people of Shu.[23]: 73

Refusing to submit to Wei (223–225)

[edit]Shortly after he became regent, he received letters from various Wei officials – including Hua Xin, Wang Lang, Chen Qun, Xu Zhi (許芝) and Zhuge Zhang (諸葛璋) – asking him to surrender to Wei and make Shu a vassal state under Wei.[Sanguozhi zhu 12] Instead of responding to any of the letters, he wrote a memo, called Zheng Yi (正議; "Exhortation to Correct Action"), as follows:

In the past, Xiang Yu did not act out of virtue, so even though he dominated Huaxia and had the might to be emperor, he died and was boiled into soup. His downfall has served as a cautionary tale for generations. Wei did not learn from this example and has followed in his footsteps. Even if they have the fortune to avoid it personally, doom will befall their sons and grandsons. Many of those who asked me to surrender to Wei are already in their old age, pushing papers in service of a pretender.

They are like Chen Chong and Sun Song, fawning on Wang Mang, even supporting him in usurping the throne, yet seeking to avoid their punishment. When Emperor Guangwu was hacking at their roots, his few thousand weakened footsoldiers were roused to tear apart Wang Mang's expeditionary force of 400,000 outside of Kunyang. When holding the Way and punishing the wicked, numbers are irrelevant.

So it was with Cao Cao, for all his craftiness and might. He raised hundreds of thousands of troops to save Zhang He at Yanping, whose potence was shriveled and choices regrettable. Barely managing to escape himself, Cao Cao brought shame to his doughty troops, and forfeited the land of Hanzhong to Liu Bei. Only then did Cao Cao realise that the Divine Vessel of imperial authority is not something to be taken at one's pleasure. Before he could finish the return journey, his poisonous intent killed him from inside. Cao Pi excels at evil, which he demonstrated by usurping the throne.

Suppose those asking my surrender were as eloquent and persuasive as Su Qin and Zhang Yi, even as far as possessing the glibness of Huan Dou who could fool Heaven itself. If they wish to slander Emperor Tang and pick apart Yu and Hou Ji, they'll just be squandering their abilities dribbling pointless ink from overworked brushes. This is something no true man or Confucian gentleman would do.

The Military Commandments say: "With 10,000 men willing to die, you can conquer the world." If in the past the Yellow Emperor – his whole forces totalling 50,000 or so – controlled every region and stabilised the whole world, how much more so by comparison could ten times his number do, holding the true Way, standing over these criminals?[Sanguozhi zhu 13]

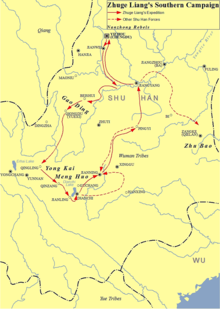

Southern Campaign (225–227)

[edit]

Zhuge Liang wanted to personally lead the Shu forces on a southern campaign to the Nanzhong region to suppress the rebellions which erupted in 223, as well as to pacify and gain the allegiance of the Nanman tribes living there. Wang Lian, Zhuge Liang's chief clerk, strongly objected to his boss's participation in the campaign because it was too dangerous. He argued that given Zhuge Liang's important status in Shu, he should not undertake such a risky venture. However, Zhuge Liang insisted on personally leading the campaign as he was worried that none of the Shu generals was competent enough to deal with the rebels on his own.[Sanguozhi 41] Ma Su, an adviser under Zhuge Liang, suggested that rather than conventional warfare, they focus on psychological warfare, winning the hearts of the people in Nanzhong, so as to prevent rebellions from breaking out again. Zhuge Liang readily accepted Ma Su's advice.[22]

In the spring of 225, Zhuge Liang led the Shu forces on the southern campaign. They defeated the rebel leaders Yong Kai (雍闓), Gao Ding (高定) and Zhu Bao (朱褒), and pacified the three commanderies of Jianning (建寧; around Qujing, Yunnan), Yuexi/Yuesui (越巂; around Xichang, Sichuan) and Zangke (牂柯; around Guiyang or Fuquan, Guizhou).[22] After that, they turned their attention to Meng Huo, a local leader who supported the rebels. Zhuge Liang knew that Meng Huo was a popular and respected figure in Nanzhong among the Nanman and local Han Chinese, so he decided to let Meng Huo live. After capturing Meng Huo in battle, Zhuge Liang showed him around the Shu camp and asked him what he thought. Meng Huo replied, "Before this, I knew nothing about your army, which was why I lost. Now that you have shown me around your camp, I know the conditions of your army and will be able to win easily." Zhuge Liang laughed, released him and allowed him to return for another battle. The same cycle repeated for a total of seven times. On the seventh time, Meng Huo surrendered and told Zhuge Liang, "My lord, against Heaven's might the people of the south will never again rebel." Zhuge Liang then led his forces towards Dian Lake in triumph.[Sanguozhi zhu 14] The Nanzhong region was basically pacified by the autumn of 225.[Sanguozhi 42]

Before pulling out all Shu soldiers from the Nanzhong region, Zhuge Liang told Meng Huo and other local leaders that all he required from them was to pay tribute to the Shu government, in the form of gold, silver, oxen, warhorses, etc. He also appointed locals such as Li Hui and Lü Kai to serve as the new commandery administrators, while the local leaders and tribal chiefs were allowed to continue governing their respective peoples and tribes.[22] After the southern campaign, the Shu state became more prosperous as the Nanzhong region became a steady source of funding and supplies for the Shu military. Under Zhuge Liang's direction, the Shu military also started training soldiers, stockpiling weapons and resources, etc., in preparation for an upcoming campaign against their rival Wei.[Sanguozhi 43]

Northern Expeditions (227–234)

[edit]Submitting the Chu Shi Biao

[edit]

In 227, Zhuge Liang ordered troops from throughout Shu to mobilise and assemble in Hanzhong Commandery in preparation for a large-scale military campaign against Cao Wei. Before leaving, he wrote a memorial, called Chu Shi Biao ("memorial on the case to go to war"), and submitted it to the Liu Shan. Among other things, the memorial contained Zhuge Liang's reasons for the campaign against Wei and his personal advice to Liu Shan on governance issues.[Sanguozhi 44] After Liu Shan approved, Zhuge Liang ordered the Shu forces to garrison at Mianyang (沔陽; present-day Mian County, Shaanxi).[Sanguozhi 45]

Tianshui revolts and Battle of Jieting

[edit]

In the spring of 228, Zhuge Liang ordered Zhao Yun and Deng Zhi to lead a detachment of troops to Ji Valley (箕谷) and pretend to attack Mei County (郿縣; southeast of Fufeng County, Shaanxi) via Xie Valley (斜谷). Their mission was to distract and hold the Wei forces' attention, while Zhuge Liang led the Shu main army to attack Mount Qi (祁山; the mountainous regions around Li County, Gansu). Upon reaching Mount Qi, Zhuge Liang deployed his troops in orderly formations and directed them with clear and strict commands. Three Wei-controlled commanderies – Nan'an (南安; around Longxi County, Gansu), Tianshui, and Anding (安定; around Zhenyuan County, Gansu) – responded to the invasion by defecting to the Shu side. News of the Shu invasion sent shockwaves throughout the Guanzhong region.[Sanguozhi 46]

The Wei government was stunned when they learnt of the Shu invasion and totally unprepared for it because they had lowered their guard against Shu after Liu Bei's death in 223 and had not heard anything from Shu since then. They were even more fearful and shocked when they heard of the three commanderies' defection.[Sanguozhi zhu 15] In response to the Shu invasion, Cao Rui moved from his imperial capital at Luoyang to Chang'an to oversee the defences in the Guanzhong region and provide backup. He sent Zhang He to attack Zhuge Liang at Mount Qi,[Sanguozhi 47] and Cao Zhen to attack Zhao Yun and Deng Zhi at Ji Valley.[Sanguozhi 48]

Zhao Yun and Deng Zhi lost to Cao Zhen at the battle in Ji Valley. Zhuge Liang had given them command of the weaker soldiers while he led the better troops to attack Mount Qi. Nevertheless, Zhao Yun managed to rally his men into putting up a firm defence as they retreated, thus minimising their losses.[Sanguozhi 48] In the meantime at Mount Qi, Zhuge Liang had put Ma Su in charge of the vanguard force to engage the enemy. At Jieting (街亭; or Jie Village, east of Qin'an County, Gansu), Ma Su not only went against Zhuge Liang's instructions, but also made the wrong moves, resulting in the Shu vanguard suffering a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Wei forces under Zhang He. Zhang He also seized the opportunity to attack and reclaim the three commanderies for Wei.[Sanguozhi 49][Sanguozhi 50]

Upon learning of the Shu defeats at Ji Valley and Jieting, Zhuge Liang pulled back the Shu forces and retreated to Hanzhong Commandery, where he resettled the few thousand families they captured in the Wei-controlled Xi County (西縣; present-day Li County, Gansu) during the campaign. This happened in the late spring of 228.[24] Zhuge Liang executed Ma Su for disobeying orders and to appease public anger.[Sanguozhi 51] Afterward, he analysed why the campaign failed and told his subordinates:

Our armies at Mount Qi and Ji Valley together were superior to the enemy in numbers, yet we lost the battles. This wasn't because we had insufficient troops, but rather, it was due to one man. Now, we should reduce the number of troops and officers, instil greater discipline in the military, and reflect on our mistakes, so as to adapt and prepare ourselves for the future. If we can't do this, it won't be helpful even if we have more troops! From today, please raise whatever concerns you may have about the State, and point out my mistakes and flaws. We can then be more decisive and be able to defeat the enemy and move closer towards victory and success.[Sanguozhi zhu 16]

He also wrote a memorial to Liu Shan, taking full responsibility for the Shu defeats at Jieting and Ji Valley, acknowledging his mistakes and failure in judgment, and requesting to be demoted by three grades as punishment.[Sanguozhi 52] Liu Shan approved and symbolically demoted him from Imperial Chancellor to General of the Right (右將軍), but allowed him to remain as acting Imperial Chancellor and continue performing the same duties as he did before.[Sanguozhi 53]

Siege of Chencang

[edit]

Between late spring and early winter of 228,[24] Zhuge Liang directed his efforts towards reorganising the Shu military, strengthening discipline, and training the troops in preparation for another campaign.[Sanguozhi zhu 17] During this time, he received news that Shu's ally Wu had defeated Wei at the Battle of Shiting around September 228.[24] From this, he deduced that the Wei defences in the Guanzhong region must be weaker because Wei had mobilised its best troops to the eastern front to fight Wu.[Sanguozhi zhu 18]

In December 228, Zhuge Liang allegedly wrote a second Chu Shi Biao to Liu Shan to urge war against Wei.[Sanguozhi zhu 19] However, historians such as Qian Dazhao (錢大昭) have cast doubts on the authenticity of the second Chu Shi Biao and argued that it is falsely attributed to Zhuge Liang. Among other discrepancies, the second Chu Shi Biao differs sharply from the first Chu Shi Biao in tone, and already mentions Zhao Yun's death when the Sanguozhi recorded that he died in 229.[Sanguozhi 54]

In the winter of 228–229, Zhuge Liang launched the second Northern Expedition and led the Shu forces out of San Pass (north of the Qin Mountains to the south of Baoji, Shaanxi) to attack the Wei fortress at Chencang (陳倉; east of Baoji). Before the campaign, Zhuge Liang already knew that Chencang was heavily fortified and difficult to capture, so when he showed up he was surprised to see that the fortress was additionally very well-defended. In fact, after the first Shu invasion, the Wei general Cao Zhen had predicted that Zhuge Liang would attack Chencang so he put Hao Zhao, a Wei general with a fierce reputation in the Guanzhong region, in charge of defending Chencang and strengthening its defences.[Sanguozhi 55][25]

Zhuge Liang first ordered his troops to surround Chencang, then sent Jin Xiang (靳詳), an old friend of Hao Zhao, to persuade Hao Zhao to surrender. Hao Zhao refused twice.[Sanguozhi zhu 20] Although Hao Zhao had only 1,000 men with him to defend Chencang, he successfully held his ground against the Shu invaders. In the subsequent 20 days of siege, Zhuge Liang used an array of tactics to attack Chencang – siege ladders, battering rams, siege towers and underground tunnels – but Hao Zhao successfully countered each of them in turn.[Sanguozhi zhu 21] After failing to outwit Hao Zhao and take Chencang, and after learning that Wei reinforcements were approaching, Zhuge Liang decided to pull back his troops and return to base.[Sanguozhi zhu 22] Wang Shuang, a Wei officer, led his men to attack the retreating Shu forces, but was killed in an ambush laid by Zhuge Liang.[Sanguozhi 56]

Battle of Jianwei

[edit]

In the spring of 229, Zhuge Liang launched the third Northern Expedition and ordered Chen Shi to lead Shu forces to attack the Wei-controlled Wudu (武都; around present-day Cheng County, Gansu) and Yinping (陰平; present-day Wen County, Gansu) commanderies. The Wei general Guo Huai led his troops to resist Chen Shi. He retreated when he heard that Zhuge Liang had led a Shu army to Jianwei (建威; in present-day Longnan, Gansu). The Shu forces then conquered Wudu and Yinping commanderies.[Sanguozhi 57][24]

When Zhuge Liang returned from the campaign, Liu Shan issued an imperial decree to congratulate him on his successes in defeating Wang Shuang during the second Northern Expedition and capturing Wudu and Yinping commanderies during the third Northern Expedition. He also restored Zhuge Liang to the position of Imperial Chancellor.[Sanguozhi 58]

Congratulating Sun Quan on becoming emperor

[edit]Around May 229,[24] Sun Quan, the ruler of Shu's ally state Wu, declared himself emperor and put himself on par with Liu Shan of Shu. When the news reached the Shu imperial court, many officials were outraged as they thought that Sun Quan had no right to be emperor, and so they urged the Shu government to break ties with Wu.[Sanguozhi zhu 23] Although Zhuge Liang agreed that Sun Quan lacked legitimacy, he considered that the Wu–Shu alliance was vital to Shu's survival and long-term interests because they needed Wu to help them keep Wei occupied in the east while they attacked Wei in the west. After concluding that Shu should maintain the Wu–Shu alliance and refrain from criticising Sun Quan,[Sanguozhi zhu 24] he sent Chen Zhen on a diplomatic mission to Wu to recognise Sun Quan's claim to the throne and congratulate him.[Sanguozhi zhu 25]

Ziwu Campaign

[edit]In August 230,[24] Cao Zhen led an army from Chang'an to attack Shu via the Ziwu Valley (子午谷). At the same time, another Wei army led by Sima Yi, acting on Cao Rui's order, advanced towards Shu from Jing Province by sailing along the Han River. The rendezvous point for Cao Zhen and Sima Yi's armies was at Nanzheng County (南鄭縣; in present-day Hanzhong, Shaanxi). Other Wei armies also prepared to attack Shu from the Xie Valley (斜谷) or Wuwei Commandery.[Sanguozhi 59]

When he heard of Wei recent movements, Zhuge Liang urged Li Yan to lead 20,000 troops to Hanzhong Commandery to defend against the Wei invasion which he reluctantly accepted after much persuasion.[Sanguozhi 60] As Xiahou Ba led the vanguard of this expedition through the 330 km Ziwu Trail (子午道), he was identified by the local residents who reported his presence to the Shu forces. Xiahou Ba barely managed to retreat after reinforcements from the main army arrived.[Sanguozhi zhu 26]

Zhuge Liang also allowed Wei Yan to lead troops behind the ennemy lines towards Yangxi (陽谿; southwest of present-day Wushan County, Gansu) to encourage the Qiang people to join Shu Han against Wei. Wei Yan greatly defeated Wei forces led by Guo Huai and Fei Yao.[Sanguozhi 61] Following those events, the conflict became a prolonged stalemate with few skirmishes. After more than a month of slow progress and by fear of significant losses and waste of resources, more and more Wei officials sent memorials to end the campaign. The situation wasn't helped by the difficult topography and constant heavy rainy weather lasting more than 30 days. Cao Rui decided to abort the campaign and recalled the officers by October 230.[24][Sanguozhi 62]

Battle of Mount Qi

[edit]

In 230,[26] Zhuge Liang launched the fourth Northern Expedition and attacked Mount Qi (祁山; the mountainous regions around present-day Li County, Gansu) again. He used the wooden ox, a mechanical device he invented, to transport food supplies to the frontline.[Sanguozhi 64] The Shu forces attacked Tianshui Commandery and surrounded Mount Qi, which was defended by the Wei officers Jia Si (賈嗣) and Wei Ping (魏平).[Jin Shu 1] At Mount Qi, Zhuge Liang managed to convince Kebineng, a Xianbei tribal leader, to support Shu in the war against Wei. Kebineng went to Beidi Commandery (北地郡; around present-day central Shaanxi) and rallied the locals to support Shu.[Sanguozhi zhu 27]

At the time, as Grand Marshal Cao Zhen was ill, Cao Rui ordered the general Sima Yi to move to Chang'an to supervise the Wei defences in the Guanzhong region against the Shu invasion. After making preparations for battle, Sima Yi, with Zhang He, Fei Yao, Dai Ling (戴陵) and Guo Huai serving as his subordinates, led Wei forces to Yumi County (隃麋縣; east of present-day Qianyang County, Shaanxi) and stationed there.[Jin Shu 2] He then left Fei Yao and Dai Ling with 4,000 troops to guard Shanggui County (上邽縣; in present-day Tianshui, Gansu), while he led the others to Mount Qi to help Jia Si and Wei Ping.[Sanguozhi zhu 28]

When Zhuge Liang learnt of the Wei forces' approach, he split his forces into two groups – one group to remain at Mount Qi while he led the other group to attack Shanggui County. He defeated Guo Huai, Fei Yao and Dai Ling in battle and ordered his troops to collect the harvest in Shanggui County. In response, Sima Yi turned back from Mount Qi, headed to Shanggui County, and reached there within two days. By then, Zhuge Liang and his men had finished harvesting the wheat and were preparing to leave.[Jin Shu 3] Zhuge Liang encountered Sima Yi at Hanyang (漢陽) to the east of Shanggui County, but they did not engage in battle: Zhuge Liang ordered his troops to make use of the terrain and get into defensive positions; Sima Yi ordered his troops to get into formation, while sending Niu Jin to lead a lightly armed cavalry detachment to Mount Qi. The standoff ended when Zhuge Liang and the Shu forces retreated to Lucheng (鹵城), took control of the hills in the north and south, and used the river as a natural barrier.[Sanguozhi zhu 29][Jin Shu 4]

Although his subordinates repeatedly urged him to attack the enemy, Sima Yi was hesitant to do so after seeing the layout of the Shu camps in the hills. However, he eventually relented when Jia Si and Wei Ping mocked him and said he would become a laughing stock if he refused to attack.[Sanguozhi zhu 30] Sima Yi then sent Zhang He to attack the Shu camp in the south, guarded by Wang Ping, while he led the others to attack Lucheng head-on.[Sanguozhi zhu 31] In response, Zhuge Liang ordered Wei Yan, Wu Ban and Gao Xiang to lead troops to engage the enemy outside Lucheng. The Wei army lost the battle, along with 3,000 troops and some equipment.[Sanguozhi zhu 32]

Despite his victory, Zhuge Liang could not make use of the momentum to launch a major offensive on the enemy because his army was running low on supplies. Sima Yi launched another attack on the Shu camps and succeeded in breaking through Zhuge Liang's defences. The Book of Jin recorded that as Zhuge and the Shu army retreated under the cover of night, Sima Yi led his forces in pursuit and inflicted over 10,000 casualties on the enemy.[Jin Shu 5] This account from the Book of Jin is disputed by historians[Jin Shu 6][27] and is not included in the 11th-century monumental chronological historical text Zizhi Tongjian.

In any case, according to Records of the Three Kingdoms and Zizhi Tongjian, Zhuge Liang retreated to the Shu because of lack of supply, not defeat,[Sanguozhi 65][28] Zhang He led his troops to attack the retreating Shu forces but fell into an ambush and lost his life.[Sanguozhi 65]

Battle of Wuzhang Plains

[edit]

In the spring of 234, Zhuge Liang led more than 100,000 Shu troops out of Xie Valley (斜谷) and camped at the Wuzhang Plains on the south bank of the Wei River near Mei County (郿縣; southeast of present-day Fufeng County, Shaanxi). Aside from using the flowing horse to transport food supplies to the frontline, he implemented a tuntian plan by ordering his troops to grow crops alongside civilians at the south bank of the Wei River. He also forbid his troops from taking the civilians' crops.[Sanguozhi 66]

In response to the Shu invasion, the Wei general Sima Yi led his forces and another 20,000 reinforcements to the Wuzhang Plains to engage the enemy. After an initial skirmish[Jin Shu 7] and a night raid on the Shu camp,[Jin Shu 8] Sima Yi received orders from the Wei emperor Cao Rui to hold his ground and refrain from engaging the Shu forces. The battle became a stalemate. During this time, Zhuge Liang made several attempts to lure Sima Yi to attack him. On one occasion, he sent women's ornaments to Sima Yi to taunt him. An apparently angry Sima Yi sought permission from Cao Rui to attack the enemy, but was denied. Cao Rui even sent Xin Pi as his special representative to the frontline to ensure that Sima Yi followed orders and remained in camp. Zhuge Liang knew that Sima Yi was pretending to be angry because he wanted to show the Wei soldiers that he would not put up with Zhuge Liang's taunting, and to ensure that his men were ready for battle.[Jin Shu 9][Sanguozhi zhu 33]

During the stalemate, when Zhuge Liang sent a messenger to meet Sima Yi, Sima Yi asked the messenger about Zhuge Liang's daily routine and living conditions. The messenger said that Zhuge Liang consumed three to four sheng of grain a day and that he micromanaged almost everything, except trivial issues like punishments for minor offences. After hearing this, Sima Yi remarked, "How can Zhuge Kongming expect to last long? He's going to die soon."[Jin Shu 10][Sanguozhi zhu 34]

Death and post-mortem events (234)

[edit]

The stalemate at the Wuzhang Plains lasted for over 100 days.[Sanguozhi 67] Sometime between 11 September and 10 October 234,[a] Zhuge Liang became critically ill and died in camp. He was 54 (by East Asian age reckoning) at the time of his death.[Sanguozhi 68]

Sun Sheng's Jin Yangqiu (晉陽秋) recorded the following account:

A glowing red meteorite fell from the sky along the northeast-to-southwest direction towards (Zhuge) Liang's camp, bounced off the ground and landed again three times, expanding in size when it bounced off and shrinking in size as it landed. (Zhuge) Liang died shortly after.[Sanguozhi zhu 35]

The Book of Wei (魏書) and Han–Jin Chunqiu (漢晉春秋) gave different accounts of where Zhuge Liang died. The former recorded that Zhuge Liang vomited blood in frustration when his army ran out of supplies during the stalemate and he ordered his troops to burn down their camp and retreat into a valley, where he fell sick and died.[Sanguozhi zhu 36] The latter recorded that he died in the residence of a certain Guo family.[Sanguozhi zhu 37] In his annotations to Zhuge Liang's biography, Pei Songzhi pointed out that the Wei Shu and Han–Jin Chunqiu accounts were wrong, and that Zhuge Liang actually died in camp at the Wuzhang Plains. He also rebutted the Wei Shu account as follows:

"It was unclear from the situation (at the Battle of Wuzhang Plains) which side was winning and which side was losing. (The Wei Shu) was exaggerating when it said that (Zhuge) Liang vomited blood. Given Kongming's brilliance, was it likely for him to vomit blood because of Zhongda?[f] This exaggeration originated from a note written by Emperor Yuan of Jin which said '(Zhuge) Liang lost the battle and vomited blood'. The reason why (the Wei Shu) said that Zhuge Liang died in a valley was because the Shu army only released news of Zhuge Liang's death after they entered the valley."[Sanguozhi zhu 38]

When Sima Yi heard from civilians that Zhuge Liang had died from illness and the Shu army had burnt down their camp and retreated, he led his troops in pursuit and caught up with them. The Shu forces, on Yang Yi and Jiang Wei's command, turned around and readied themselves for battle. Sima Yi pulled back his troops and retreated. Some days later, while surveying the remains of the Shu camp, Sima Yi remarked, "What a genius he was!"[Sanguozhi 69] Based on his observations that the Shu army made a hasty retreat, he concluded that Zhuge Liang had indeed died, so he led his troops in pursuit again. When Sima Yi reached Chi'an (赤岸), he asked the civilians living there about Zhuge Liang and heard that there was a recent popular saying: "A dead Zhuge (Liang) scares away a living Zhongda[f]" He laughed and said, "I can predict the thoughts of the living but I can't predict the dead's."[Sanguozhi zhu 39][Jin Shu 11]

Burial and posthumous honours

[edit]

Before his death, Zhuge Liang said that he wanted to be buried as simply as possible in Mount Dingjun (in present-day Mian County, Hanzhong, Shaanxi): his tomb should be just large enough for his coffin to fit in; he was to be dressed in the clothes he wore when he died; he did not need to be buried with any decorative objects or ornaments.[Sanguozhi 70] Liu Shan issued an imperial edict to mourn and eulogise Zhuge Liang, as well as to confer on him the posthumous title "Marquis Zhongwu" (忠武侯; "loyal martial marquis").[Sanguozhi 71]

Zhuge Liang once wrote a memorial to Liu Shan as follows and kept his promise until his death:[Sanguozhi 72]

"(I have) 800 mulberry trees and 15 qing of farmland in Chengdu, and my family have more than enough to feed and clothe themselves. When I am away (from Chengdu) on assignment, I do not incur any excess expenses. I depend solely on my official salary for my personal expenses. I do not run any private enterprises to generate additional income. If I have any excess silk and wealth at the time of my death, I would have let Your Majesty down."[Sanguozhi 73]

In the spring of 263, Liu Shan ordered a memorial temple for Zhuge Liang to be built in Mianyang County (沔陽縣; present-day Mian County, Shaanxi).[Sanguozhi 74] Initially, when Zhuge Liang died in 234, many people wanted the Shu government to build memorial temple to honour him. However, after some discussion, the government decided not to because it was not in accordance with Confucian rules of propriety. In his works, Sima Guang noted that during the Han era, only emperors were worshiped at temples.[29] With no official channels to worship Zhuge Liang, the people took to holding their own private memorial services for Zhuge Liang on special occasions. Some time later, some people pointed out that it was appropriate to build a memorial temple for Zhuge Liang in Chengdu, but the Shu emperor Liu Shan refused. Two officials, Xi Long (習隆) and Xiang Chong, then wrote a memorial to Liu Shan and managed to convince him to build the memorial temple in Mianyang County.[Sanguozhi zhu 40]

In the autumn of 263, during the Wei invasion of Shu, the Wei general Zhong Hui passed by Zhuge Liang's memorial temple in Mianyang County along the way and paid his respects there. He also ordered his troops to refrain from farming and logging anywhere near Zhuge Liang's tomb at Mount Dingjun.[Sanguozhi 75]

Guo Chong's five anecdotes

[edit]The Shu Ji (蜀記), by Wang Yin (王隱), recorded that sometime in the early Jin dynasty, Sima Jun (司馬駿; 232–286), the Prince of Fufeng (扶風王), once had a discussion about Zhuge Liang with his subordinates Liu Bao (劉寶), Huan Xi (桓隰) and others. Many of them brought up negative points about Zhuge Liang: making a bad choice when he chose to serve under Liu Bei; creating unnecessary burden and stress for the people of Shu; being overly ambitious; and lacking awareness about the limits of his strengths and abilities. However, there was one Guo Chong (郭沖) who dissented and argued that Zhuge Liang's brilliance and wisdom exceeded that of Guan Zhong and Yan Ying. He then shared five anecdotes about Zhuge Liang which he claimed nobody had heard of. Liu Bao, Huan Xi and the others fell silent after hearing the five anecdotes. Sima Jun even generously endorsed the five anecdotes by Guo Chong.[Sanguozhi zhu 41]

Pei Songzhi, when annotating Zhuge Liang's official biography in the Sanguozhi, found the five anecdotes unreliable and questionable, but he still added them into Zhuge Liang's biography and pointed out the problems in each of them.[Sanguozhi zhu 42] In his concluding remarks, Pei Songzhi noted that the fourth-century historians Sun Sheng and Xi Zuochi, given their attention to detail, most probably came across Guo Chong's five anecdotes while doing research on the Three Kingdoms period. He surmised that Sun Sheng and Xi Zuochi probably omitted the anecdotes in their writings because they, like him, also found the anecdotes unreliable and questionable.[Sanguozhi zhu 43]

Harsh laws

[edit]In the first anecdote, Guo Chong claimed that Zhuge Liang incurred much resentment from the people when he implemented harsh and draconian laws in Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing). Fa Zheng, an adviser to Liu Bei, tried to dissuade Zhuge Liang from doing so as he believed that the harsh and draconian laws would drive a wedge between the people of Yi Province and Liu Bei's government. He further pointed out that the government lacked popular support and political legitimacy at the time because some people saw Liu Bei as a foreign invader who occupied Yi Province by military force. Fa Zheng then urged Zhuge Liang to relax the laws and give the people some "breathing space".[Sanguozhi zhu 44] In response, Zhuge Liang argued that harsh laws were necessary to restore law and order in Yi Province and help Liu Bei's government consolidate its control over the territories and people. He blamed Liu Yan's 'soft' rule and Liu Zhang's incompetence for allowing corruption and decadence to become deeply entrenched in Yi Province. He also argued that the best way to set things right was to restore law and order and to regulate the distribution of honours and privileges among the population.[Sanguozhi zhu 45]

Pei Songzhi pointed out three problems in this anecdote. First, when Fa Zheng and Liu Bei were still alive, Zhuge Liang was never in a position powerful enough for him to implement such a policy; he would have to be the Governor of Yi Province (益州牧) to do so, but he only became Governor of Yi Province (in addition to other appointments) during Liu Shan's reign. Second, as Zhuge Liang is known for being a respectful, humble and faithful subject, it seemed totally out of place for him to advocate such a policy and make such a crude response to Fa Zheng. Third, good governance, which Zhuge Liang is known for, is not normally associated with harsh laws.[Sanguozhi zhu 46]

Assassination attempt on Liu Bei

[edit]In the second anecdote, Guo Chong claimed that Cao Cao once sent an assassin to kill Liu Bei. When the assassin first met Liu Bei, he could only speak to Liu Bei from a distance, so he thought of a way to attract Liu Bei's attention and get up close. He started analysing the situation in Cao Cao's domain and presented ideas to Liu Bei on how to attack it. Liu Bei found his ideas interesting and asked him to come closer. Just then, Zhuge Liang came into the meeting room and caused the assassin to panic. He noticed the assassin's facial expression and found him suspicious. The assassin then excused himself, saying that he needed to use the latrine, Liu Bei told Zhuge Liang, "I found an extraordinary man who can be a good assistant to you." When Zhuge Liang asked who it was, Liu Bei said, "The man who just went to the latrine." Zhuge Liang took a deep breath and said, "Just now, I saw a look of fear and panic on his face. His avoidance of eye contact and his body language show that he has something evil on his mind. He must be an assassin sent by Cao Cao." Liu Bei immediately ordered the assassin's arrest but the assassin had already fled.[Sanguozhi zhu 47]

Pei Songzhi pointed out the problems in this anecdote. If this incident really happened, the assassin must be a great talent to be able to attract Liu Bei's attention and, in Liu Bei's opinion, worthy enough to serve as an assistant to Zhuge Liang. However, this was unlikely because assassins were typically rough and boorish men ready to sacrifice their lives to accomplish their mission. Besides, it did not make much sense for a man of such talent to be an assassin when he could be better off as an adviser to any of the great warlords. Moreover, as Cao Cao was known for respecting and cherishing talents, it was unlikely that he would willingly sacrifice someone of such talent by sending him on a risky mission. Furthermore, given the significance of this incident, it should be recorded in history, but there is no mention of it in the official histories.[Sanguozhi zhu 48]

Empty Fort Strategy

[edit]

Guo Chong's third anecdote concerns Zhuge Liang's alleged use of the Empty Fort Strategy against Sima Yi at Yangping (陽平).[Sanguozhi zhu 49]

Rejecting compliments

[edit]In the fourth anecdote, Guo Chong claimed that when Zhuge Liang returned to Chengdu after the first Northern Expedition, he received many compliments from his colleagues for his successes in capturing a few thousand Wei families and making Jiang Wei defect to Shu. However, to their surprise, Zhuge Liang solemnly replied, "All the people under Heaven are people of the Han Empire. Now, the Han Empire isn't revived yet and the people are still suffering from war. It will be my fault even if only one person dies due to war. I dare not accept compliments built on people's miseries." The people of Shu then realised that his goal was to vanquish Wei rather than simply expanding Shu's borders through conquests.[Sanguozhi zhu 50]

Pei Songzhi pointed out that Zhuge Liang's goal of achieving a complete victory over Wei was already well known before he went on the first Northern Expedition, so it seemed very odd for Guo Chong to say that the people of Shu only realised it after Zhuge Liang came back from the first Northern Expedition. He also noted that the first Northern Expedition was an overall failure so the "successes" mentioned in this anecdote neither made sense nor were worthy of compliments. The reasons he gave were as such: Shu lost two battles against Wei in the first Northern Expedition and ultimately failed to conquer the three commanderies; Wei had nothing to lose from the defection of Jiang Wei, who at the time was a relative nobody; and the capture of the few thousand Wei families was insufficient to make up for the casualties the Shu forces suffered at Jieting and Ji Valley.[Sanguozhi zhu 51]

Earning the trust of soldiers

[edit]In the fifth anecdote, Guo Chong claimed that during the fourth Northern Expedition, when Zhuge Liang led Shu forces to attack Mount Qi, the Wei emperor Cao Rui decided to launch a counterattack on Shu, so he personally led his forces to Chang'an. He then ordered Sima Yi and Zhang He to lead 300,000 elite Wei soldiers from Yong and Liang provinces on a covert operation deep into Shu territory and launch a stealth attack on Jiange (劍閣; in present-day Jiange County, Sichuan), a strategic mountain pass. Around the time, Zhuge Liang had set up a rotating shift system, in which at any time 20 percent of his troops (about 80,000 men) would be stationed at Mount Qi, while the remaining 80 percent would remain behind. As the Wei forces approached Mount Qi and prepared to attack the Shu positions, Zhuge Liang's subordinates urged him to stop the rotating shift system and concentrate all the Shu forces together to resist the numerically superior Wei forces. Zhuge Liang replied, "When I lead the troops into battle, I operate on the basis of trust. Even the ancients felt it was a shame for one to betray others' trust in him in order to achieve his goals. The soldiers who are due to return home can pack up their belongings and prepare to leave. Their wives have been counting the days and looking forward to their husbands coming home. Even though we are in a difficult and dangerous situation now, we shouldn't break our earlier promise." When the homebound soldiers heard that they were allowed to go home, their morale shot up and they became more motivated to stay back and fight the Wei forces before going home. They talked among themselves and pledged to use their lives to repay Zhuge Liang's kindness. Later, during the battle, they fought fiercely and killed Zhang He and forced Sima Yi to retreat. Zhuge Liang won the battle because he successfully gained the trust of the Shu soldiers.[Sanguozhi zhu 52]

Pei Songzhi pointed out that this anecdote contradicted the accounts from historical records. During the fourth Northern Expedition, Cao Rui was indeed at Chang'an, but he did not personally lead Wei forces into battle. As for the part about Cao Rui ordering Sima Yi and Zhang He to lead a 300,000-strong army to attack Jiange, Pei Songzhi argued that it never happened because it was extremely unlikely for such a large army to pass through the Guanzhong region, bypass Zhuge Liang's position at Mount Qi, and enter Shu territory completely undetected. He also found the part about the rotating shift system untrue because it was impossible for a Shu expeditionary force to enter Wei territory and remain there for so long, much less set up a rotating shift system.[Sanguozhi zhu 53]

Family and descendants

[edit]| Zhuge family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Spouse

Zhuge Liang married the daughter of Huang Chengyan, a reclusive scholar living south of the Han River. The Xiangyang Ji (襄陽記) recorded that Huang Chengyan once asked Zhuge Liang, "I heard you are looking for a wife. I have an ugly daughter with yellow hair and dark skin, but her talent matches yours." Zhuge Liang then married Huang Chengyan's daughter. At the time, there was a saying in their village: "Don't be like Kongming when you choose a wife. He ended up with [Huang Chengyan]'s ugly daughter."[Sanguozhi zhu 54] Although her name was not recorded in history, she is commonly referred to in popular culture by the name "Huang Yueying" (黃月英).

- Children

- Zhuge Qiao (諸葛喬; 199–223), Zhuge Liang's nephew and adopted son. As Zhuge Liang initially had no son, he adopted Zhuge Qiao, the second son of his elder brother Zhuge Jin. Zhuge Qiao served as a military officer in Shu and died relatively early.[Sanguozhi 76]

- Zhuge Zhan (諸葛瞻; 227–263), Zhuge Liang's first son. He served as a military general in Shu and married a daughter of the Shu emperor Liu Shan. He was killed in battle in 263 during the Wei invasion of Shu.[Sanguozhi 77]

- Zhuge Huai (諸葛懷), Zhuge Liang's third son. He is mentioned only in the Zhuge Family Genealogy (諸葛氏譜) cited in the 1960 publication Collected Works of Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮集). In 269, during the Jin dynasty, Emperor Wu summoned the descendants of famous Han dynasty officials (e.g. Xiao He, Cao Shen) to the imperial court so that he could confer honorary titles on them. When Zhuge Liang's descendants did not show up, Emperor Wu sent his officials to find them. The officials found Zhuge Huai in Chengdu and brought him to Emperor Wu. Zhuge Huai declined the honour, saying that he was contented with the land and property he already owned at the time. Emperor Wu was pleased and he did not force Zhuge Huai to accept.[30]

- Zhuge Guo (諸葛果), Zhuge Liang's daughter. She is mentioned only in the 1960 publication Collected Works of Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮集) and the Ming dynasty Daoist text Lidai Shenxian Tongjian (歷代神仙通鑑; Comprehensive Mirror on Immortals Through the Dynasties). Her father named her guo (果; "fulfil / realise", basic meaning "fruit / result") because he wanted her to learn Daoist magical arts and fulfil her destiny of becoming an immortal.[31]

- Grandchildren and great-grandchildren

- Zhuge Pan (諸葛攀), Zhuge Qiao's son. In 253, after Zhuge Ke (Zhuge Jin's first son) and his family were exterminated in a coup d'état in Eastern Wu, Zhuge Pan reverted from his adopted lineage (Zhuge Liang's) to his biological lineage (Zhuge Jin's) and went to Eastern Wu to continue Zhuge Jin's family line there.[Sanguozhi 78]

- Zhuge Shang (諸葛尚; died 263), Zhuge Zhan's eldest son. He was killed in battle in 263 alongside his father during the Wei invasion of Shu.[Sanguozhi 79]

- Zhuge Jing (諸葛京), Zhuge Zhan's second son. After the fall of Shu, he moved to Hedong Commandery in 264 together with Zhuge Pan's son, Zhuge Xian (諸葛顯), and later served as an official under the Jin dynasty after being summoned in c.April 269.[Sanguozhi 80][Sanguozhi zhu 55][Jin Shu 12]

- Zhuge Zhi (諸葛質), a son of Zhuge Zhan. He is mentioned only in the Zaji (雜記) cited in the 1960 publication Collected Works of Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮集). After the fall of Shu, Liu Xun (劉恂; a son of Liu Shan) was unwilling to accompany his father to Luoyang, so he sent Zhuge Zhi as a messenger to meet Meng Qiu (孟虬), Meng Huo's son, and seek permission to live with the Nanman tribes. Meng Qiu approved.[32]

- Others

- Zhuge Dan (諸葛誕; died 258), a cousin of Zhuge Liang, served in Cao Wei as a high-ranking military general in the mid Three Kingdoms period. Between 257 and 258, he started a rebellion in Shouchun against the Wei regent Sima Zhao, but ended up being defeated and killed.[Sanguozhi 81]

Appraisal and legacy

[edit]

Holding power as a regent

[edit]After Liu Bei's death, Liu Shan ascended to the throne of Shu Han. He granted Zhuge Liang the title "Marquis of Wu District" (武鄉侯) and created an office for him as a Chancellor. Not long later, Zhuge Liang was appointed Governor of Yi Province – the region which included most of Shu Han's territory.

Being both the Chancellor (directly managing the bureaucrat officers) and provincial governor (directly managing the common people) meant that both the magistrates and common people – all civil affairs in Yi Province – were in the hands of Zhuge Liang. Having an independent Chancellery Office with attached independent subordinates meant that Zhuge Liang's authority was relatively independent of the emperor's authority. In other words, just as attested in Sanguozhi, all of Shu Han's affairs, trivial or vital, were directly handled by Zhuge Liang, and the emperor Liu Shan was just a nominal leader. Moreover, the emperor himself was strictly educated and supervised by Zhuge Liang. This situation was maintained until Liang's death.

There are many attempts who tried to explain why Zhuge Liang refused to return the authority to Liu Shan. Yi Zhongtian proposed three reasons:[33]: ch.37

- Zhuge Liang supported the model of the emperor only indirectly lead the country and have a Chancellor to handle the affairs in his name, similar to the situation during the Western Han. In his opinion, if the emperor directly handled the affairs, then there would be no one to blame if problems occurred, but a Chancellor could bear responsibility and punishment for failure.

- Zhuge Liang stubbornly thought that Liu Shan was not experienced enough to directly handle the state affairs, considered too important to risk error.

- The situation of Shu Han was indeed very complicated at that time which required extremely well-planned solutions. An inexperienced Liu Shan could not handle such challenging problems, but Zhuge Liang could.

Economic reforms

[edit]Yi Province's wealthy families, unchecked by previous governors, freely exploited the common people and lived in extravagance. As a result, poverty was widespread, and economic–political reform was the most important concern for Zhuge Liang. A robust economic foundation was also necessary to enhance the people's loyalty to Shu Han regime and properly support the future's expeditions against Cao Wei. Therefore, Zhuge Liang made it clear that the core value of his policy was to stabilize and improve the life of the people.[34]

Zhuge Liang's new policies were enacted during the reign of Liu Bei and continued in the time of Liu Shan. He purged corrupt officials, reduced taxes, and restricted the aristocracy's abuse of power against the common people. Corvée labour and military mobilization were also reduced and rescheduled to avoid the disruption of agriculture activities, and Cao Cao's tuntian system of state-run agricultural colonies was implemented extensively to increase food production output. Agriculture dykes were significantly rebuilt and repaired, including the eponymous Zhuge dyke north of Chengdu. Thanks to the reforms, Shu Han agriculture production grew significantly, sufficient to sustain an active military.

Salt manufacture, silk production, and steelmaking – three major industries in Shu – also attracted Zhuge Liang's attention. Liu Bei, following the proposal of Zhuge Liang, created specialized bureaus for managing salt and steel manufacture, initially directed by Wang Lian and Zhang Yi, respectively. A specialized silk management bureau was also established, and silk production experienced significant growth, leading to Chengdu being nicknamed "the city of Silk". Over the lifetime of the Shu Han state, it accumulated 200,000 pieces of silk in the national treasury. Sanguozhi reported that salt production in Shu Han was highly prosperous and generated significant income to the government. Fu Yuan, a well-known local metalsmith, was appointed to a role in metallurgy research by Zhuge Liang, and managed to improve the techniques in crafting steel weapons for the Shu Han army.